Hello Muse Readers!

In the past few years of “pandemic life” we have seen large shifts in the way that many of us go about our lives in terms of our work, family/friend/societal interactions, education, medical care, travel, shopping, etc. In the midst of these changes, many of us have developed new habits and hobbies, like putting more time into fixing up/tweaking our living spaces and yards, buying more indoor plants, reading more books, and writing more handwritten letters.

During the initial months of the pandemic when people were in quarantine/lockdown, the online sale of stationery products (notecards, writing paper, envelopes, etc.) jumped over 300%, and this trend has continued even after life has somewhat returned to normal. In a world of excessive screen time—Zoom, Skype, Netflix, Prime Video, social media platforms, video games, internet browsing—letter writing can be categorized as “slow communication,” and mental health experts agree that the revival of the art of the handwritten letter is not only calming in a frenetic digital world, but it also offers other benefits:

Stimulates creativity—Placing pen to paper utilizes the visual, motor, and cognitive brain processes in a different way than when we type on a computer or phone. Handwriting also requires us to slow down and connect our minds with our hands, creating a sensory experience that stimulates our brains to think in a more creative manner.

Boosts mood and reduces stress—When we write a letter to someone, we often include both the ups and downs of our current state of being. In writing about the highs, our brains release mood boosting chemicals, and in writing about the lows, we are reflecting on our current issues and getting them off our chests. In recounting what has been happening in our day-to-day existence, we can arrive at greater clarity when it comes to goals, meaning, and priorities.

Creates joy and serendipity—In general, writing a letter makes us feel good and gives us a sense of accomplishment. We’ve picked out a lovely notecard or piece of stationery, we’ve written something thoughtful, and we’ve focused on each word as we communicate. And, the person on the receiving end will find a surprise in their mailbox.

Provides a needed break from technology and multitasking—Most of us would agree that we need lengthy breaks from our screens and from the constant stimulation and distraction of flitting from website to website or from Facebook to Twitter to Instagram. Sitting down to write a letter relaxes and focuses our minds on the task at hand—interpersonal communication.

Gives us a tangible memory—Unlike digital communication (emails and texts), handwritten letters are real. We can put them in a drawer, in a scrapbook, in a special box. We can pick them up from time to time and reread them, feel and hear the sound of the paper. It might sound sentimental, but we may imagine someone in a hundred years finding our letters in an attic and reading them with fascination.

Consider surprising someone this week with a handwritten letter. Even dropping a friend or family member a note saying, “Just thinking of you” or “Glad you are in my life” will be a happy surprise for the recipient.

Maybe pen a letter to yourself, which you will open in the future, perhaps offering words of encouragement. It has also become a trend to write a future letter to your children or grandchildren to be opened when you are deceased. Or you can write a letter to someone who is deceased—this can be a cathartic act. Once the letter is completed, you can tuck it away or perhaps burn it.

By spending intentional and focused time writing letters, we not only experience the benefits listed above, but we open ourselves to a deeper satisfaction not always present when we quickly type an email or send a brief text message.

****

We so appreciate your support of our small press! Thank you for subscribing to the Weekly Muse! If you come across any issues involving the Muse or if you have any questions, you can email us at:

Not a Vacation Planet: The Environment / Climate

Poet Joy Harjo said, “This is not a vacation planet”—meaning: we must show up and do the work to make the changes in the world we want to see. And between climate issues and endangered animals and deforestation, we have a lot on our minds!

Brainstorm a list of the things that you worry about in regards to the climate, environment, or in the natural world. Maybe it’s aggressive hurricanes, the wildfires in your area, erosion, or the sea-level rise. Write everything that concern you environmentally.

Now, look at all of the topics you have listed and choose one that has some energy and interest around it—something that feels important for you to write about.

For this prompt, imagine you are a painter and you can only paint a picture of the topic you have chosen. Convey through images how you want to communicate to another person your feelings about your environmental / climatic / natural issue.

For example, if you live on the West Coast and choose the ongoing wildfires and living in a world where you can’t open your window due to smoke, you wouldn’t write a “telling” statement such as, “Wildfires are bad for our air quality” or “I hate the ongoing wildfires in my state” but something like, “Outside my throat burns during two months of wildfires…” or “The sky is wildfire pink, a haze of the blackening forests…”

Describe the climate or environmental issue through concrete images so that your poem is “showing” rather than “telling.” Use active verbs as you create your vivid descriptions.

Here are two tips:

Sometimes the best way to make someone hear you is by whispering.

Sometimes a poem wants to be a poem, not a soapbox.

And once you’ve finished your poem, check out “Where to Submit Your Work” for two places looking for environmental/climate poems. Also, read our interview below with poet Todd Davis who offers advice for poets writing about the natural world.

Interview with Todd Davis: Remembering that all living beings are our kin

TSP: Todd, along with touching on other themes, your seventh book, Coffin Honey, highlights the natural world and the consequences of our abuse of it. For example, in your poem “Lost Blue” the speaker counts what fish are left after a wildfire and your line drones replace the shadows of birds from your poem “What the Market Will Bear” is such a haunting image of a future world. How does your relationship with the natural world continue to inform your work and how do you write about the harder topics?

TD: Through evolution, through all the sacred stories of the greater-than-human world, through the science that demonstrates we literally cannot live without the other living beings that make up the world, that shape it, that create the air we breathe, the food we eat, the water we drink, even the microbial life on our skin or in our gut, with this knowledge and lived history, I can’t imagine a life outside of the intimate blessings of the natural world, the lessons it has to teach, and what it asks of me in return, what I must try to give back in reciprocity. That’s always on my mind.

Within this context, my writing is informed by the knowledge of the radical degradation of the world we’re witnessing at present, by the greed that drives so much of this degradation and the Sixth Wave of extinction, by the systems that widen the gulf between humans and so many other species.

But if that was the only thing that informed my writing, I’d simply slip into despair. My poems are also influenced by, inspired by, what’s left, what continues to struggle to survive or even thrive in this moment.

To the west of my home in Pennsylvania sits 41,000 acres of state game lands along the Allegheny Front. It was radically abused in the late 19th and 20th century—clear-cut, deep-tunnel mined for coal, and later strip-mined for coal. It’s made a remarkable recovery over the past 70 years, and today this forest is home to native brook trout, kingfisher and great blue heron, eagles and osprey, hermit thrushes and all sorts of warblers, deer, bear, fox, beaver, fisher, bobcat, coyote, mink, and a good array of wildflowers and trees, among my favorites, ginseng and lady’s slipper, tulip poplar and chestnut oak.

Coffin Honey was a difficult book to write, one that was an expression of grief and trauma and violence that includes the story of a young boy who is the victim of sexual abuse and assault. The poems seek to make the connection between how we treat the most vulnerable—human and more-than-human—and the spiritual and physical health of the world we are part of. How do we find healing? How do we express our grief? How do we repair our relationship to the earth? How do we show gratitude, and what is required of us to give back?

As a writer, I must write back toward these questions and stories with honesty, with clarity. To evade such questions, to elide the parts of the stories where I’d simply like to look away, feels like a betrayal. But I grieved hard as I wrote this boy’s story, as I tried to represent the young woman who finds herself pregnant, her boyfriend deployed with the military, as I presented possible futures in which we continue to ignore the collapse of ecosystems, the remaking of the world with climate catastrophe. In my poem, “Extinction,” I write, Dear Prophecy, please don’t come true. And that’s my hope. That we learn to coexist in sustainable ways. That species adapt in ways we can’t anticipate. That we turn away from our screens and spend a little more time fully present to the gift of this world.

TSP: You spend a lot of time outdoors, so we were curious if you carry a notebook or journal to document what you see or what you do to remember images? Also, what advice do you have for poets writing about the natural world and the environment?

TD: Part of my writing process is to be in the woods, to be on small rivers and creeks, bushwhacking or following game trails or old logging roads up the mountain. Paying attention to the ways the land heals itself, the scars that are left. Being in relationship with the flora and fauna, watching its daily change, its weekly and seasonal shifts.

I’ve been fortunate to live in one place for the past 20 years, to have those decades of close observation. Simply showing up to observe, to be a part of a such a place, provides many amazing experiences and encounters.

So, yes, I carry a notebook and jot lines as they come to me, observational notes. What does the air feel like today? Air has sensuous qualities and brings news of weather or of an animal’s approach or some new blossom or some new death. What tree is in the process of leafing? What do those earlier versions of the leaf look like? Recording when certain flowers appear. We have a host of spring ephemerals, and I visit particular places in the woods when I know—within a few days—they should first flower. Carolina spring beauties and foam flower and fringed polygala, to name a few whose company I look forward to during the winter months, anticipating spring. I also carry a camera, taking photos of anything that captures my attention, snapping away from many different angles. I don’t want the camera to replace language or being present in the moment, but I find in examining the photos later I discover aspects of the species or scene that I might have missed.

As for advice, remembering that all living beings are our kin, our relatives, that we share so much genetic material with the creatures that move, seen and unseen, around us. But also to remember that these other living creatures have a different perspective, a different way of being in the world. How to honor them as we use our imagination to make the leap across certain fluid boundaries? We don’t simply want to remake them in our own image. Yet to deny the emotional life of a river otter, for example, seems wrong, too. It’s a complex negotiation to represent these more-than-human lives in our language.

What’s required of a poet who writes about nature, I think, is a long apprenticeship to these other lives. Learning what science can teach us about them. Learning what direct observation might teach us. Learning from other artists—painters and writers and sculptors—who have tried to express these lives. Then being quiet and listening, allowing them to speak to us in their own ways.

About Todd:

Todd Davis is the author of seven books of poetry, most recently Coffin Honey and Native Species, both published by Michigan State University Press. He has won the Midwest Book Award, the Foreword INDIES Book of the Year Bronze and Silver Awards, the Gwendolyn Brooks Poetry Prize, the Chautauqua Editors Prize, and the Bloomsburg University Book Prize. His poems appear in such noted journals and magazines as Alaska Quarterly Review, American Poetry Review, Gettysburg Review, Iowa Review, Missouri Review, North American Review, Orion, and Western Humanities Review. He teaches environmental studies at Pennsylvania State University’s Altoona College.

Learn more about Todd at : http://www.todddavispoet.com

Purchase Todd’s latest book Coffin Honey on Amazon by clicking here.

****

For Questions to the Editors: email any questions you have about writing poems, submitting your work, book contests, etc. to: and we will choose a question to answer every other week!

365 Black-Eyed Peas

For this week’s poetry exercise, you have an opportunity to cook up a poem in which you mix together food and superstition. Maybe you are familiar with some superstitious beliefs that center around food on a cultural level or perhaps there are some odd superstitions held only within your immediate family. You are also free to completely make up a superstition that involves food in some manner.

Here are just a few food-related superstitions from a variety of cultural backgrounds:

If you are newly married, don’t feed your spouse chicken wings or he/she/they might fly away.

In order to make a wart disappear, cut open a potato, rub it on the wart, wrap the potato in an old dishtowel, and bury it in your yard.

On New Year’s Day, eat 12 round fruits and you will have 12 months of prosperity.

If your child has a bad cough, steal milk and bread from a neighbor and feed it to your child. This will cure the cough.

Don’t eat rice from a small dish in the presence of those you respect. It will cause them to reject you.

Buy a bottle of bourbon before your wedding day to ensure good weather.

For a prosperous year, eat collard greens, pork, and 365 black-eyed peas on New Year’s Day.

Don’t eat both ends of a loaf of bread before you eat the middle of the loaf. This will bring about poverty.

You can use one of the above food superstitions as a launching point for your poem or you can do a little internet research to find some other ideas. Another option (which might be the most fun) is to completely create your own food-related belief. Maybe in your poem, a drop of honey and a pinch of salt placed under the pillow of your significant other on Valentine’s Day eve will bring about a year of bliss in your relationship. The sky is the limit as far as the interesting and unique ideas you can come up with!

Our example poem is “Dish of Mashed Peas” by Susan Terris. In this wonderfully playful piece, Terris presents a superstition involving mashed peas placed in the light of the moon, though the instructions haven’t been provided for guaranteeing happiness and good luck. The poem concludes with a heartwarming reference to the speaker’s deceased grandmother, who found happiness in a well-baked cake.

Dish of Mashed Peas

Some people are not destined for happiness,

and I may be one of them.

You see, in certain parts of the world where

I have been and now live,

at least in my dreams, happiness is only

granted to a woman

who leaves a dish of mashed peas out in

the moonlight overnight.

But superstition does not name what moon

phase or if one must

eat the peas. Instructions too vague.

Peas uneaten. Moon dark.

No happiness yet. I’d ask my nana if she

were still here,

but she was the one who gauged oven heat

with a bent elbow

and said happiness was to bake a cake

until done.

****

Inspired by Terris, write a poem that puts forth a superstition involving food. If you would like, bring in a family member with whom you have (or may have had) a strong bond. Be imaginative and creative, and consider using your “superstition food” in your title.

The Place To Be

The Latin term genius loci is translated as “the spirit of a place” and was a widely used expression in the ancient world, especially in pre-Christian Roman religion. The term referred to the belief that places were imbued with a particular “spirit” which could be honored, and which gave the place an energy, certain characteristics, and a personality that was almost interactive.

The genius loci in today’s world is what we would describe as the atmosphere, ambience, and the emotions, thoughts, and sensations that arise in us when we are in a certain place or locale. Remember the decaying Victorian house on the corner and whenever you walked by you felt goosebumps, creeped out, and you had a feeling you were being watched? Or maybe when you visited a sacred Hopi site in Arizona you felt an incredible calm and awe, a tinge of sorrow, a sense of holiness and history, and you thought you heard small voices in the breeze. Perhaps when you stood on the shore of Lake Michigan during a storm you felt expansiveness, a feeling of adventure, fearfulness at the power of the water roiling in the wind, and an unnamed mightiness. The genius loci can even make itself known in your response to the homes of friends and family—when you step into some houses you feel comfortable and warm while other abodes might cause you to feel uneasy and cold.

As poets and writers, most of us are fascinated with the nuances of place. We want our poems, stories, and essays to fully describe a given location so that our readers feel as if they are there. In our writing, we often make connections between an outer landscape and our interior mood or state.

For this week’s journal exercise you will be making two lists of places (aim to include at least five to eight—or more—places in each list). In the first list come up with places where you had an overwhelming positive experience—a feeling of wholeness, excitement, awe, peacefulness, as if this place was really you and you could imagine thriving there. In the second list, jot down places where you felt a deep sadness, isolation, emptiness, uncomfortableness as if you didn’t want to spend too much time in that location.

Pick one place from each category and write a paragraph vividly describing these places and your experiences in them. Get specific with details about the locations and fully describe what was going on within you—thoughts, emotions, sensations, etc.

Let you paragraphs sit unread for a week or two and then go back and reread them. Which one jumps out at you most and inspires you? Consider using the material in one of your paragraphs (or both!) for a poem or essay.

*This journal exercise was inspired by writer Linda Lappin.

Two Sylvias Press Wilder Poetry Book Prize is Open for Submissions

Are you a woman poet over fifty years of age?

Check out The Two Sylvias Press Wilder Poetry Book Prize awarded each year to a woman poet over fifty for her full-length poetry collection:

$1000 prize and a vintage, art nouveau pendant

Open to established and emerging poets

Past winners: Carmen Gillespie, Adrian Blevins, Dana Roeser, Erica Bodwell, Gail Martin, Michelle Bitting, and Gail Griffin

Submissions are open from Sept. 1 - Dec. 31

Read the complete guidelines by visiting our website: https://twosylviaspress.com/wilder-series-poetry-book-prize.html

Literature in the News

Published last week in Slate Magazine:

“She’s 80 Years Old, She’s Furious, and She Just Published Her First Book”

You might say that, at 80 years old, Jane Campbell is a literary late bloomer. But you also might say, as the poet Sharon Olds once did, that “anyone who blooms at all, ever, is very lucky.” Fresh off the late-summer publication of Cat Brushing, her well-reviewed book of short stories, Campbell spoke to Slate about being an 80-year-old debut author and why more angry, sexy old ladies is exactly what the publishing industry needs.

Jane Campbell: Dorothy Sayers wrote, a long time ago, a paper, “Are Women Human?” She was trying to persuade the patriarchal world, which was even worse in her day, that women were people, that they were human beings. And I think that old women are kind of othered in a curiously destructive way, in a way that probably old men aren’t. Are they quite human? Are they subhuman? Are they full human beings? And what I wanted to say, from quite an angry point of view, was, yes, old women are totally functioning human beings...

Read this wonderful interview with Jane Campbell on Slate’s website by clicking here.

Muse Trivia

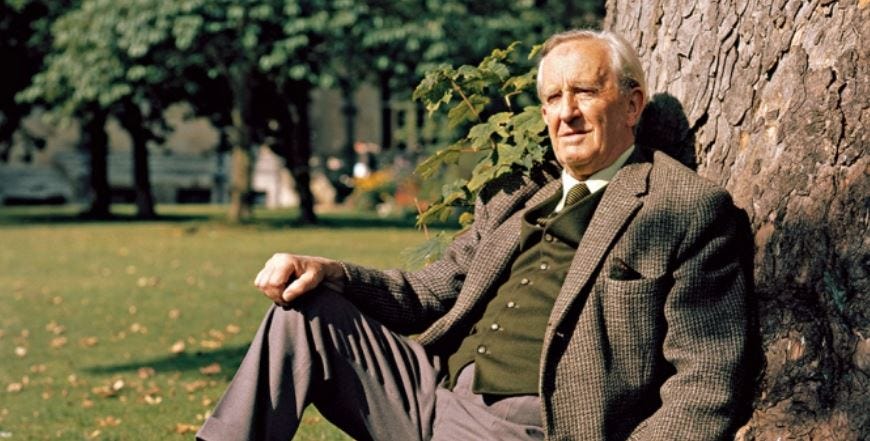

J.R.R. Tolkien, legendary author of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings trilogy, was well known for being a jokester. He sometimes dressed as an Anglo-Saxon warrior and would chase a few of his neighbors around their yards. While lecturing to his students at Oxford, he would occasionally take a four-inch green shoe from his pocket and proclaim that it was “proof that leprechauns exist.”

One time Tolkien and his best buddy C.S. Lewis went to a serious event dressed as polar bears. When he was elderly, Tolkien would often initially hand shopkeepers a pair of false teeth before giving them money for his items.

Treehouse Climate Action Poem Prize from Academy of American Poets / Deadline: November 15, 2022 Reading Fee 0 / Prizes: $1000, $750, $500 From Poets.org: In addition, all three poems will be published in the popular Poem-a-Day series, which is distributed to 500,000 readers. Poems may also be featured in the award-winning education series Teach This Poem, which serves 37,000 educators each week. Judges: Climate scientist and author Dr. Peter Kalmus and poet Mattew Olzmann https://poets.org/treehouse-climate-action-poem-prize-guidelines Simultaneous submissions–Yes! Fugue / Deadline: November 1, 2022 Reading fee: $3 Send 3-5 poems From the editors: Send us your risks and outcasts, your vulnerable, transparent, and revealing constructions. Send us your resistances, spells, and curses. Send us your poems that embrace the unknown, your poems from monsters and to monsters. We want freshness—the poems that disrupt language, startle, surprise, and engage with the world like no other. https://fugue.submittable.com/submit Simultaneous submissions–Yes! Canary Magazine / RE-OPENS November 1, 2022 and closes when they reach their number of submissions Reading fee: $3 / Looking for winter-themed work that focuses on environmental issues such as climate change and loss of species/greenspace/etc. #ProTip: Submit early! https://canarylitmag.org/submissions.php Simultaneous submissions–Yes!

Opposite Day!

There is a funny Seinfeld episode where George Costanza realizes all of his choices, instincts, and decisions in life have been wrong, so he decides to do the opposite. (Hilariously, things start going well for this curmudgeonly character by his creation of The Costanza Rule: When To Ignore Your Instincts And Do The Opposite.) So this week we ask—what would your poems look like if you composed them differently, tried a few new things? Or what if you did the exact opposite of your instincts and what you would normally write?

Poet Kathleen Flenniken has said about her poems that sometimes when she is revising them, she uses an opposite word as a replacement. For example, if you were to write, I stood on the grass thinking about life… then your revision might be, I kneeled on the sky thinking about death. This revision creates a very surreal moment in the poem, yet still is grounded in image. You could also revise it as, I kneeled on the grass and didn’t think about death, or I stood on the sky thinking about life.

So many times we can fall into the routines of our lives, but what would happen if we tried the opposite of what we normally do? Do you need to stretch beyond your comfort zone? Do you need to write in a way you haven’t written before? Is there something out in the world you want to try but have been afraid to?

We end this week honoring that we may not always know what is best for ourselves. Consider making space for the opposite choices—a parallel universe where you may wear black while your poet-self may choose white, and yet both choices are okay.

Using “opposites” is one more tool for your poetic toolbox and can allow an element of play and surprise to enter into your writing.

Thanks for writing with us!

Please consider joining our private group of Weekly Muse subscribers on Facebook in order to share your thoughts on writing, your poems, your challenges, your successes, etc. Request to join here:

We would also love to share your successes in this section of the Weekly Muse. Please send along any publication good news to:

Have a wonderful week!

Kelli & Annette

Cofounders & Coeditors of Two Sylvias Press