Hello Writers and Creatives!

A poet on Twitter recently tweeted that “poetry is dead” because there are so many other forms of communication and entertainment available. She attributed poetry’s death to the digital world and social media, but in a surprising twist, she implied that it’s time for poetry to leave the room—it’s had a good run, but as a literary art, it’s appeal and usefulness have ceased.

The responses to this tweet were interesting. Poets, writers, and book lovers pushed back, tweeting that poetry is still indeed relevant, beloved, popular, and that the digital world has helped people learn to write poems and has made poetry more accessible. Poets and non-poets alike strongly voiced their opposition to the notion that poetry is (and should be) a thing of the past.

The next morning, following the “poetry is dead” tweet, the New Yorker happened to publish an in-depth interview with poet Jorie Graham in which she was asked, “Could poetry go extinct?” Graham gave an interesting and insightful response:

The one thing about a poem that has always amazed me is this strange way it has of being alive. Whatever small market exists for it, it cannot really be bought or sold or transacted, as in reality it doesn’t have a unique material existence. Its nature is of a different kind. It inhabits another kind of space and time. Every copy of Keats’s “To Autumn” is the original. And, if every copy of that poem on planet Earth were incinerated, it would remain just as alive, intact, original, and “in reality” if it is located in just one person’s memory… Poems cannot easily go the way of the ivory-billed woodpecker… And they will be there for us if we come back to them, if we dig them out of the rubble, or recover them from one human mind.

Poems will be one of the very last things to go extinct. They are near-indestructible—and if we are smart they will never depend on technology-enabled platforms alone to exist. Because, as long as one human mind has Keats’s “Ode,” it is as alive and new as it ever was and ever will be…

What simple action can we take to rally against the “poetry is dead” sentiment and to embody Jorie Graham’s statement that poetry can never “go extinct” as long as a single human mind remembers a poem? We’d like to suggest that you take the time to memorize a poem this month!

Choose a poem you find inspiring, and set about memorizing it (and if it’s particularly lengthy, memorize a few of your favorite stanzas or sections). Even if you’ve already memorized some beloved poems, choose a new one to learn by heart. Memorization not only strengthens and exercises your mind, but the poem you have memorized will rattle around in your subconscious as you write your own poems—it will supply you with rhythms, themes, and poetic devices.

And when you are bored and standing in line at the post office, don’t grab your phone to begin aimlessly scrolling—silently recite your memorized poem and allow it to trigger new ideas for your next writing session!

Have a wonderful week!

*****

We so appreciate your support of our small press! Thank you for subscribing to the Weekly Muse! If you come across any issues involving the Muse or if you have any questions, you can email us at: twosylviasweeklymuse@gmail.com

Poem Inspired by a Quote

For this week’s prompt, we’re going to write a poem in response to this quote: I want to change skin: tear the old one from me.

Allow that quote to simmer in your mind for a bit and see what comes of it—does this quote mean you want to be someone else or you hope the world will change you? Are you wishing for a desperate change or maybe you’re feeling like you want to press back against this quote and not change skin.

As you consider this quote, you may just want to begin by freewriting or journaling on the quote and allow your mind to wander until you feel the poem kick in.

As you respond to this quote, perhaps choose one of these topics to focus on more specifically: identity (How do we, as unique individuals, navigate a world that doesn’t necessarily conform to us? What does it mean to be an individual in a society?); gender (How important is our gender to our sense of self? Is gender fixed, fluid, or subject to change? Why is gender important? Is it?); trauma & recovery (How has trauma shaped you? What obstacles or challenges have you overcome? What obstacles stand in your way? How has society pushed you down, and how have you gotten back up?); creative expression (Why write? Why take photographs? Where does the artistic impulse come from? Does art have a purpose beyond its existence? Is it self-expression? If not, then what is it?); or intuition & dreams (Do they inform or influence you or your work? Are they integral to your survival as a human being?)

See what this quote brings up for you and follow that inkling. Remember, there is no wrong way to do this prompt. Just allow this quote to inform your poem, however you see fit.

If you need an opening line to begin, consider one of the following:

When I heard…

If I wanted/needed/could…

Maybe I’ll…

Because I…

And once you’ve written your poem, check out our “Places to Submit Your Work” section below as there is a new online literary journal called Exist Otherwise which wants poems that are inspired by that quote!

Interview with Kathy Fagan: The Poetry of Writing into Questions Without Expecting Answers

TSP: Kathy, it’s been five years since your incredible book Sycamore (Milkweed, 2017) was published and we have been anxiously awaiting your next book, Bad Hobby (Milkweed, 2022). We are so thrilled that it’s out in the world—and it definitely does not disappoint! It’s such a deep and fulfilling read as your voice is one of the most engaging around.

One of the gifts of a Kathy Fagan poem is it can tell a story without telling a story—meaning, you so seamlessly move from image to image through a poem so that when the reader gets to the end, it’s as if a rich embroidery has been created in the mind’s eye. In Bad Hobby, several of your poems come with moments of both poignancy and humor while you move (what appears effortlessly!) between present and past writing about family, caring for an aging father with dementia, and childhood along with integrating the natural world. These can be difficult topics to write about for many reasons, but you do it with such grace, thoughtfulness, and depth, all while keeping the reader captivated with each poem.

We have many readers trying to write about childhood, caretaking or illness, as well family/parents—what advice do you have for poets trying navigate these topics?

KF: First of all, thank you for reading both Sycamore and Bad Hobby so closely and warmly. You are such a generous member of the poetry community, and I am grateful for you and your poems.

I think of Bad Hobby as a memoir in verse. It’s the most autobiographical book I’ve published, and I struggled with the difficulties you mention exactly because of the personal nature of the material. I asked myself throughout the writing of these poems—the oldest poem in the book was written in 2014 and the most recent in 2021—if I had the “right” to use family material, I questioned my reasons for including it in my work, and, most pressing of all, I wondered how I’d make real poems from it, distinct from more reportorial or diaristic impulses, especially as I was living it moment by moment.

Two things guided me through. One was a good therapist, whom I’m lucky to know. Of course, we discussed the childhood material thoroughly. I ranted to and wept with her the years my dad lived with me, becoming more ill, combative, and dependent weekly. My mother also died during this time; there was a lot to grieve and integrate, as well as serious financial implications. Because of therapy, the poems didn’t have to share the burden of that articulated processing; I could make poems as I always had, writing into questions without expecting answers, writing into juxtapositions for the sheer joy of discovering what they might bring forth, pushing on language to yield a thing adjacent to my direct experience but not the experience itself: a new experience, the poem as new experience. In that way the poems became not me, not my trauma, not my sadness, not my shame or anger or inadequacies: the poems now belonged to anyone who might find and read them. Just today I read a wonderful essay on stamina in poetry by Carl Phillips, who puts this another way, quoting Ellen Bryant Voigt: “Poetry is not the transcription but the transformation of experience.”

The second thing that helped shape Bad Hobby was reading a lot of creative nonfiction, primarily lyric essays and memoir, and learning how to weave history, the natural world, cultural criticism, and other details into the larger fabric of self. When I say “self,” I’m aware of its construction, that the speaker in our writing is never static because we’re in flux all the time. That notion alone helped me to distance myself from my material just enough to avoid the dreaded pitfalls of self-pity and sentimentality—mostly. Revision helped with those issues, too, as it always does. Lyric essays and memoirs gave me permission, in other words, to tell my story in a way that might also best engage others; with their emphasis on research, the primacy of the sentence, clarity, and awareness of audience, these writers taught me how to work unwieldy and difficult narrative material into my poems.

An extremely short list of some especially instructive nonfiction writers for me includes Rebecca Solnit, Sabrina Orah Mark (also a poet), Natasha Trethewey (same), Camille Dungy (same), Cathy Park Hong (same), Valeria Luiselli, Joan Didion, and Doireann Ni Ghriofa, and there are many others whose work I cherish.

TSP: We’re curious as to what your writing life looks like and if you have a dedicated writing space. Also, what is one tip you recommend for poets having trouble getting started on a poem?

KF: When I was finally forced to move my dad into memory care in 2019, I made a space for myself that I now use exclusively as a studio. I can make all the mess I want, with books, papers, pictures, and found objects everywhere and not worry about getting in anyone’s way or anyone getting in mine. During lockdown it doubled as a classroom while I taught remotely, and I still use it as a work/writing space. For better or worse, I don’t find it necessary to keep the two—making a living and making a poem—separate anymore. But then again, my job, especially since stepping away from admin, is teaching poetry, and I’m fortunate to work, in several ways, for and at the craft I love every day.

That said, I’m not a writer with a dedicated writing schedule. I don’t have hours set aside each day or week for it. It’s essential for me to work toward writing nearly every day, by reading a lot and taking notes, by thinking about poems while I do housework and work out and garden, but I’ve learned to be patient with what I call my poem-brain, which my life simply doesn’t permit me to access every day. Typically, when I find a few free hours to string together and the quotidian isn’t pressing down too hard, I look through my notes and something will open for me there, spurring me forward to find a line or sound or image to build on. Dwelling in that moment can be a days- or weeks-long process, sometimes resulting in a new poem. Other times the poem will draft itself more urgently. I know people who are more rigorous in their writing practice, and I’m always interested to hear how that works for them. I’m also aware that it can be equally generative to live one’s life while drawing poems from it with patience. For me, when enough fallow weeks go by and I haven’t made any lines, instead of fretting like I used to, I try novelty. This can be as simple as a trip to the rock store or deep dive into research on the internet or a change in location. Looking at pictures, following a new or abiding obsession, bringing yourself fully to a sensory experience: these can often wake up my dozing poem-brain just enough to engage with writing again.

****

About Bad Hobby:

From Kingsley Tufts Award finalist Kathy Fagan comes Bad Hobby, a perceptive collection focused on memory, class, and might-have-beens.

In a working-class family that considers sensitivity a “fatal diagnosis,” how does a child grow up to be a poet? What happens when a body “meant to bend & breed” opts not to, then finds itself performing the labor of care regardless? Why do we think our “common griefs” so singular? Bad Hobby is a hard-earned meditation on questions like these—a dreamscape speckled with swans, ghosts, and weather updates.

Fagan writes with a kind of practical empathy, lamenting pain and brutality while knowing, also, their inevitability. A dementing father, a squirrel limp in the talons of a hawk, a “child who won’t ever get born”: with age, Fagan posits, the impact of ordeals like these changes. Loss becomes instructive. Solitude becomes a shared experience. “You think your one life precious—”

And Bad Hobby thinks—hard. About lineage, about caregiving. About time. It paces “inside its head, gazing skyward for a noun or phrase to / shatter the glass of our locked cars & save us.” And it does want to save us, or at least lift us, even in the face of immense bleakness, or loneliness, or the body changing, failing. “Don’t worry, baby,” Fagan tells us, the sparrow at her window. “We’re okay.”

Best link(s) for Kathy’s book: https://milkweed.org/book/bad-hobby

Author website: http://kathyfagan.net

Facebook: Kathy Fagan Grandinetti or Kathy’s Author Page

Twitter: @KathyFaganPoet

Instagram: @poemkat

For related prose by Kathy on the web: https://www.passagesnorth.com/passagesnorthcom/2021/3/12/haircut-by-kathy-fagan

https://www.riverteethjournal.com/blog/2021/05/31/notes-to-my-father

For Kathy’s audiobook https://www.audible.com/pd/Bad-Hobby-Audiobook/B0BF72VH11

About Kathy:

Kathy Fagan’s sixth poetry collection is Bad Hobby (Milkweed Editions, 2022). Her previous book, Sycamore (Milkweed, 2017), was a finalist for the 2018 Kingsley Tufts Award. She’s been awarded a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship, an Ingram Merrill fellowship, residencies at The Frost Place, Yaddo and MacDowell, and was named Ohio Poet of the Year for 2017. Fagan’s work has appeared in venues such as The New York Times Sunday Magazine, Poetry, The Nation, The New Republic, Kenyon Review, The Academy of American Poets Poem-A-Day, The Pushcart Prize Anthology and Best American Poetry. She co-founded the MFA Program at The Ohio State University, where she teaches poetry and co-edits the Wheeler Poetry Prize Book Series for The Journal and OSU Press.

****

For Questions to the Editors: email any questions you have about writing poems, submitting your work, book contests, etc. to: twosylviasweeklymuse@gmail.com and we will choose a question to answer every other week!

Sending My Magenta Eyeliner to Mars

Since we’re at the beginning of 2023 and continuing to reflect on 2022, this week’s poetry exercise invites you to write a poem about what you would like to “banish” or get rid of from this past year (on a material level and/or a psychological/emotional level). Perhaps you had some life-changing situations arise—a divorce became finalized in September, and you’d like to erase that old life as you struggle to begin an existence without a partner. On a lighter note, maybe you bought some new clothes last spring, and you realize they make you look ten years older, so you’d like to get them out of your closet by donating them to Goodwill. Maybe you had a difficult time with self-esteem when it came to your writing life last year, and you would like to bury the negative voices which over-edit your poems and mock your creative ideas.

For most of us, there is probably a multitude of things that happened in 2022 (large and small, important and trivial) that we’d like to put in the trash bin and be done with. Your poem can focus on one thing you would like to discard or several items. You may want to create a “list poem” in which you list many things you want to get rid of as 2023 begins to unfold.

Speaking of lists, it might be helpful to take few moments to reflect on your year and to create a list of what you’d like to banish from 2022. Your list might include illness, loss, bad decisions, negative attitudes and habits, friendships that went awry, clothes, the wrong-colored lipstick, the pile of junk mail dating from the summer that you haven’ yet thrown away, etc.

This week’s example poem is by Naomi Shihab Nye. In “Burning the Old Year,” she names the items she will discard as she places them on a fire—clearing her way to begin a fresh year. Nye chooses to focus on items that are more tangible and not intrinsically important, such as notes from friends and shopping lists, as she concludes her piece by lamenting what she didn’t do in the past year:

Burning the Old Year

Letters swallow themselves in seconds.

Notes friends tied to the doorknob,

transparent scarlet paper,

sizzle like moth wings,

marry the air.

So much of any year is flammable,

lists of vegetables, partial poems.

Orange swirling flame of days,

so little is a stone.

Where there was something and suddenly isn’t,

an absence shouts, celebrates, leaves a space.

I begin again with the smallest numbers.

Quick dance, shuffle of losses and leaves,

only the things I didn’t do

crackle after the blazing dies.

****

Drawing inspiration from “Burning the Old Year,” write a poem that banishes and gets rid of things in your life from 2022—material items and/or psychological/emotional items. Choose your method of getting rid of the item(s): fire, trash, donation, garbage disposal in the sink, flushing down the toilet, burying in the ground, or more imaginatively, sending it/them via rocket to Mars, making it/them disappear with your new magic wand, mailing it/them “special delivery” to Antarctica, etc.

You can follow Nye’s formatting if you would like—writing in tercets (three-line stanzas) with relatively short lines. And consider mentioning your method of disposal in your title: “Feeding My Inner Critique to the Wolves,” “Burying My Divorce Under the Rhododendron,” etc.

What Do You REALLY Love About Writing?

Sometimes we need to take a moment to check in with our “writer self” in order to understand the details of why we desire to write. We can forget the reasons we love to write as we get caught up in finding the time to sit and compose our poems, seeking valuable feedback on our work, revising our poems, searching out places to submit our work, putting together manuscripts, marketing our chapbooks, etc. And sometimes our reasons for writing morph on a subconscious level, and it’s helpful to take some introspective time to discover these changes.

Below is a list of reasons that writers have given for why they love to write. In your journal, jot down the reasons which speak to you on a personal level when it comes to your passion for your writing. Be honest with yourself (no one else needs to see your “reasons”), so don’t shy away from choosing reasons that have to do with recognition and/or money.

Why Write?

I like telling a good story through my poetry/writing

It’s a journey of self-discovery

I can create imaginary worlds

Personal satisfaction

Sharing my life experience with others

Giving words to experiences/thoughts that are difficult to explain

Stepping into someone else’s shoes (a “persona poem” or creating a character)

My writing provides escapism from the real world

Recognition of my talent

Wordplay and exploring different styles and formatting options

Personal healing

Writing is a challenge and gives me a sense of accomplishment

Sharing the lessons I’ve learned and the discoveries I’ve made

Winning writing awards

Creating metaphors and similes

Telling my own truth

Communicating with others

Looking deeper into life

Having an audience

Making people laugh

To give me a purpose

Giving readings and interacting

I love symbols and imagery

I want to have a published book I can hold in my hands

Expressing my passion for certain subjects

Wanting to share a vision and/or message

Making some money on my writing

Wanting to help and/or inspire others

Wanting to be part of a community of writers

To explore in writing the things I don’t fully understand

Other:_____________________________________________

Other:_____________________________________________

Once you are finished, look over your list and place your selections into the following three categories—things that have to do with the PROCESS of writing, your MOTIVATION for writing, and the RESULTS you hope for upon sharing your writing.

It’s ok if your “reasons” aren’t equally distributed among the three categories. Perhaps you might write without much desire for publication and recognition, so you will have fewer items in the RESULTS category.

If you find that the bulk of your reasons fall into PROCESS, consider giving yourself more time to write so that you can fully explore different poetic devices, formatting options, and perhaps try some experimental poetry. If RESULTS seem to jump out at you as important, maybe explore more ways to get your poetry published, marketing options, and look into giving more readings—in real life and online. Get yourself out there in the poetry world!

As you look at your MOTIVATION reasons, consider delving more deeply into what topics/experiences inspire you to write—spend more time researching and reflecting on these topics/experiences and how you can transform them into poems or short stories.

Hopefully this exercise has given you some clarity when it comes to why you write. Take note of your “reasons”—what truly motivates you, the parts of the writing process you enjoy, and how you can more effectively share your writing with others.

*This exercise is inspired by writer Kathrin Lake

Two Sylvias Press News

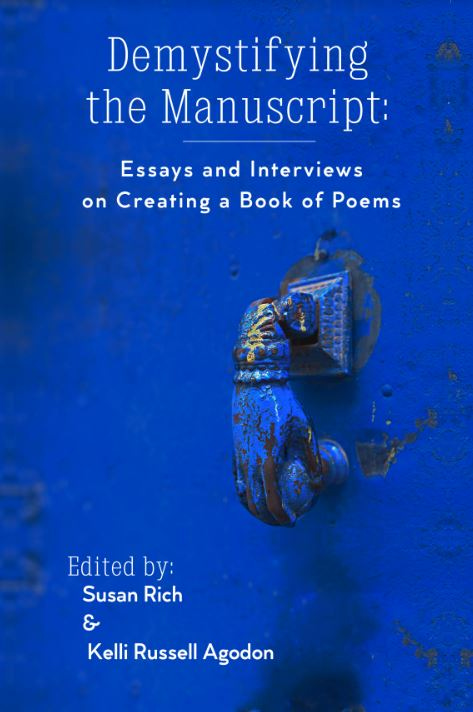

Available in Early Spring from Two Sylvias Press: Demystifying the Manuscript: Essays and Interviews on Creating a Book of Poems (edited by Susan Rich and Kelli Russell Agodon)!

Book creation is an art and Demystifying the Manuscript offers many perspectives on how to put together a book of poems through the essays and interviews of contemporary prize-winning poets and editors. While there isn’t a single “correct” method for creating a book of poems, Demystifying the Manuscript is filled with expert advice on all aspects of manuscript creation: ordering your poems, determining your goals, insider tips from the editors of journals and small presses, and everything in between. Demystifying the Manuscript will guide you through the process of creating your best book of poems whether you are an emerging writer or an established poet.

Contributors include Sandra Beasley, Nickole Brown, Lauren Camp, Oliver de la Paz, Lee Herrick, Su Hwang, Claudia Castro Luna, January Gill O’Neil, Linda Pastan, Spencer Reece, Diane Seuss, Jeff Shotts, Maggie Smith, and Melissa Studdard.

Demystifying the Manuscript is edited by Kelli Russell Agodon (cofounder/coeditor of Two Sylvias Press and the Weekly Muse) and Susan Rich (Weekly Muse subscriber and close friend of Two Sylvias).

Pre-Order your copy of Demystifying the Manuscript on our website by clicking here!

Muse Trivia

It took James Joyce nearly 17 years to write his notoriously difficult novel Finnegan’s Wake. When we say “difficult” we are referring to the fact that most readers need an accompanying guide to decipher many of the sentences: Sniffer of carrion, premature gravedigger, seeker of the nest of evil in the bosom of a good word, you, who sleep at our vigil and fast for our feast, you with your dislocated reason, have cutely foretold, a jophet in your own absence…

Part of the reason it took Joyce 17 years to finish this novel involves his poor and failing eyesight. In order to write, Joyce would lay on his stomach with the paper in front of his face. He wrote with brightly colored crayons so that he could see the letters, and he wore a white overcoat because he believed the white reflected more light onto the page in front of him.

Exist Otherwise / Ongoing Accepting poems—poems based on certain themes. The current theme is the quote in this week's prompt: I want to change skin: tear the old one from me, but they are also accepting poems not based on this theme. Editor: Eric Jennings Reading Fee: 0 / Payment $10 (Paying Market!) https://existotherwise.cc/submit/ New Market Alert: The Indy Correspondent / Deadline: Ongoing The Indy Correspondent is now open for poem submission. Email Dan Grossman up to 5 poems at: dan@indycorrespondent.org #ProTip: Accessible poems tend to do better in this type of a market. This is a great way to extend your audience and have your poems in front of readers who aren’t poets themselves. While based in Greater Indy (Indianapolis), they are open to ALL poets! Indy Correspondent: https://www.indycorrespondent.org/ Just Opened: Robert Phillips Poetry Chapbook Prize (from Texas Review Press / Deadline: April 20, 2023 Open: January 1 - March 31 Reading Fee: $20 / Prize $500 http://texasreviewpress.org/submissions/robert-phillips-poetry-chapbook-prize National Poetry Series Full-Length Manuscripts / Deadline: March 15, 2023 Reading Fee: $35 / Prize $10,000 and publication 48-64 pages is suggested & NO acknowledgments or name/identifying info in your manuscript. #ProTip: While the reading fee is higher than some, they choose 5 manuscripts to be published by prestigious presses and offer one of the highest prizes at $10,000 per winner. https://thenationalpoetryseries.submittable.com/submit Learn more here: About the National Poetry Series Woodberry Poetry Room Creative Fellowship / Deadline: February 1, 2023 Reading Fee: 0 / Fellowship prize $5000 + Writing Residency The fellowship includes: a stipend of $5,000, access to the Woodberry Poetry Room (and several other Harvard special collections), and research support from the Poetry Room curatorial staff). Writing Residency May-October. #ProTip: Prepare a project description, a curriculum vitae, a work sample, but NO letter of reference is required. Eligibility: The Creative Fellowship program invites applications from individuals (and collaborative teams) from an array of disciplines, including poets, writers, translators, filmmakers, visual artists, sound artists, composers, musicians, scholars, and digital humanitarians. We welcome submissions from applicants representing a wide range of perspectives, demographics, aesthetics, causes, and questions. The fellowship is open to candidates of all nationalities. (While non-U.S. citizens awarded a fellowship are required to obtain a J-1 visa, Harvard University can help sponsor the visa. Fellows will be responsible for paying any visa-related fees). https://library.harvard.edu/grants-fellowships/woodberry-poetry-room-fellowship#about *Please Note: This issue is longer than usual and your email provider may not load the entire contents. You might see a message below that says [Message Clipped] and a link that says “View entire message”—click the link to read the entire Muse issue on our Substack webpage.

In The New Year: In Spite of Everything, We Begin

Poet Barbara Crooker reminds us in her poem “The New Year” that no matter the challenges, the bottles of champagne that won’t be uncorked for us, and even while “the prize-winning envelope has someone else's name/on it,” we continue to write and do our work.

Below is Crooker’s poem, speaking to our lives as poets:

This poem reminds us that through rejections, feeling insignificant or overlooked, and through all of life’s challenges, you can persevere as a writer just by returning to your desk and writing.

So much of our writing life is subjective—Is this good or good enough? Will my book win an award? Will my poem be published? But while many times we do not control the outcome, we control the action, which is to write.

Sometimes as poets we may ask, Does what I’m doing matter? And the answer is yes, writing is a hopeful act.

Thea Fiore-Bloom, a writer and believer in the benefits of creativity, shared a story that while visual artist Olena Ellis was setting up her art exhibit, a class of sixth graders and their teacher wandered into the gallery. Ellis’s show featured an abacus of goddesses from a piece called “Do You Count?” A piece she made to humanize individual women battling against domestic violence and sexual exploitation in her community and in the world.

The teacher was explaining how museum patrons could put money into the jar for one of the goddesses, and the funds would be donated by Ellis to a specific, nearby, domestic violence shelter.

As the teacher said this, a young boy spoke up and said that he and his mom had stayed at that same shelter Ellis named in the description. His friend turned to him and said, “I didn’t know that about you.” Another girl in his class turned to him to offer support and then another. The nurturing atmosphere between these children was palpable.

The teacher then explained to Ellis that they do not talk about topics like this in the classroom, but her exhibition gave them the opportunity to discuss it.

Olena Ellis commented, “As artists, we are given this platform to talk about subjects that others find difficult to voice, subjects that need more light shed on them.” And it’s the same thing for poets. Your work opens doors to subjects or topics that make people feel less alone, inviting conversation. And many times, the more difficult topics are the ones that readers connect with as it makes them feel less alone.

Ellis suggests you ask yourself this:

If I bypassed my own fear of ridicule; if I followed my own heart without reservation, what would I create?

As you begin 2023, ask yourself, What would you create if self-consciousness wasn’t an issue? What are the poems you need to write? And what are the poem that only YOU can write?

As you write your poems, continue to follow your internal instincts and write about deeper topics as well as your obsessions. See 2023 as the year to really take some risks in your work—surprise yourself and see what happens!

And remember, as you send your poems out into the world, most times you never know the effect your work is having on someone. You do not know if your poem was shared with another or pinned above a desk. Most times, unless a reader writes or talks with you, you do not know what work your poem is doing in the world and who it touched and who resonated with it. And maybe part of your job as a poet is to just trust that your poem is out in the world meeting people, helping them along their journey.

There is a trust involved with art—our poems do matter.

As we move into the new year, remember there is a reason you are reading this, that you want to write poetry. It’s not the most common thing to be a poet—trust that your desire to write is within you for a reason. Trust that your poems matter in the world, because they do.

May your 2023 dazzle and surprise you in all the best ways, and may you always make room for poetry, art, and joy. May this be your best year yet! And may you always make time to begin a new poem!

Subscriber News and Inspiration

Muse Subscriber Carey Taylor writes to us with some wonderful publication news and some Muse feedback that warms our hearts:

Hi Kelli and Annette,

As this new year begins I want to first give gratitude to Two Sylvias Press and how it has been a constant joy in my poetry life this past year. It has been welcomed every week (although not always read every week, but always, eventually). Thank you for all the time and effort it must take to produce the Muse. It is often the recipe I need when it seems my creative juices have boiled away. May you both have a fruitful and peaceful 2023.

On another note, I would like to share a bit of poetry news that I am quite thrilled about. I had a poem accepted into an anthology published by the Black Spring Press Group in London. They have produced an anthology on the war in Ukraine, and my poem “Before the Cameras Leave Ukraine” was not only selected to be one of 47 represented, but the title to my poem, also became the title for the anthology. 100% of all the proceeds for this anthology go to the Sanctuary Foundation which is a charity that helps Ukrainian people to safety and homes in the UK. I have attached a link below to the press, which in turn links to pre-orders on Amazon UK:

One of my personal goals for this new year is to write more poetry that becomes a mechanism for doing good in the world. This was a grand way to start out 2023.

Such amazing and inspiring news, Carey! Thank you so much for letting us know about this anthology and the charity which will benefit from its publication and sales!

****

Martha Silano’s manuscript was a finalist for the Vassar Miller Prize! Fantastic news and many congrats!

****

Muse Subscriber Sylvia Pollack has shared her publication news with us! One of her poems was an Editor’s Choice in Quartet Journal:

My poem “Miroku Bosatsu” was an editor’s Choice in the winter issue of Quartet. The poem and my commentary on it [can be found by clicking here]. The journal is easiest to read in a browser. My poem is the final one in this issue, right before the concluding interview.

Special thanks to my Poet’s on the Coast sisters, Gail Braune Comorat and Jane C. Miller, who are two of the Quartet editors, for this beautiful and always interesting journal.

Happy New Year! I’m already looking forward to this year’s newsletters.

Congratulations on your publication (and “Editor’s Choice”), Sylvia! Wishing you an inspiring New Year filled with poems!

Please consider joining our private group of Weekly Muse subscribers on Facebook in order to share your thoughts on writing, your poems, your challenges, your successes, etc. Request to join here: https://www.facebook.com/groups/216486693984454

We would also love to share your successes in this section of the Weekly Muse. Please send along any publication good news to: twosylviasweeklymuse@gmail.com

Have a wonderful week!

Kelli & Annette

Fabulous news Carey, I am so excited for you. It is a privilege to be in a writing group with you.

And that made me think of Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451. Thank you